Parish Registers are a vital record set; without them, there is little hope of tracing an Ancestor back further than the mid 19th Century.

WHY ARE THEY SO IMPORTANT?

There are 5 record sets that all researchers should use when tracing their English ancestors; these are:

- Family oral histories, old bibles, etc

- Census records

- Civil registration records

- Parish registers

- Probate records

The first three are not limited to a certain demographic – they cover the whole population, with Civil Registration records (births, marriages, deaths) being the most reliable. However, the first three do not exist prior to 1837, making Parish Registers and Probate records very important – but – Probate records exist for only a small portion of the population through time, as not everyone left a Will. Therefore, Parish Registers are the only major source that exists for individuals prior to the 19th Century.

WHAT ARE THEY?

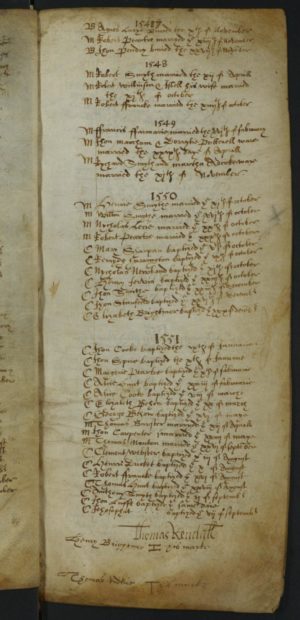

Parish registers are a record of all baptisms (or christenings), marriages and burials in a parish which began in 1538 after an Act devised by Thomas Cromwell, the Vicar General to King Henry VIII.

Many of the clergy were highly suspicious of the reasons behind the Act, thinking it was a way to raise taxes – and so they didn’t take too much care in how they recorded these events; sometimes just writing them on loose pieces of paper which were then lost, or destroyed by fire, flood, etc.

In 1598, after reigning forty years, Queen Elizabeth ordered that all parish registers were to be kept in durable parchment books, with this New Act also stating that events since her reign began in 1558, were to be Copied into these new books, but this wasn’t an easy task. Not all clergymen were able to locate their predecessor’s parish records, and some didn’t fancy copying 40 years worth into new books either. In fact, many priests began to fill out these new books starting from the first year of their own incumbency.

If you have ever researched in parish registers extensively, you’re probably thinking right now “so that’s why one parish starts at this time, and another parish at this time”. Added to the inconsistency in the keeping of the parish register during these early years, you have to also remember that through time, many pages and registers have withered away, war has destroyed some, fire, flood and other natural disasters have occurred and even some parish register books have been stolen and sold on the black market!

Only 7% of original registers have survived back to 1538 – that’s about 800 from over 11,400 parishes.

Take heart however, because the Act of 1598 also required that a transcript of the previous year’s entries be made within a month of Easter, then sent to the bishop of the diocese. These Bishop’s Transcripts (BT’s) might be the only record that survives from your ancestor’s parish, and they often predate some surviving parish registers.

WHAT DO THEY TELL US?

The first parish registers don’t tell us much, i.e. from the beginning in 1538 up to the late 1700’s. During these early years, sometimes the only information recorded was the person’s name; usually (but not always) the mother’s name was on a baptism, sometimes the person’s age when buried. You will be fortunate to find a parish parson or clerk who recorded more than was required – and also one who had good handwriting and good spelling! These were true phonetic spelling days, and also the days of abbreviated names, therefore it is very important to expand your own knowledge on the structure of early parish registers, as well as the terminology used in those early times – not to mention the handwriting and the use of Latin and Greek.

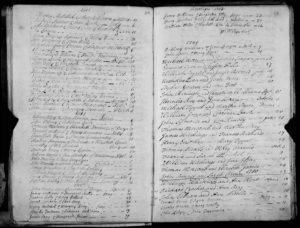

Above: A page from the baptism book of the parish of Ascombe, Devon, dated 1653. Damaged from time and moisture, only half the names are now legible. In this instance, one would search, and hope to find, the Bishop’s Transripts for this parish and time.

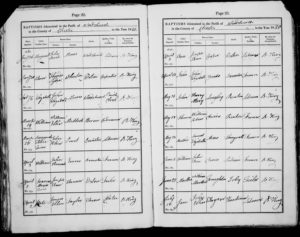

Above: A page from the parish marriage register of Gwennap, Cornwall, dated 1746-1749. In much better condition than that of Adcombe further above, this page records the names of both parties and the date they married.

ROSE’S Act 1812

In 1812 a man named George Rose amended the Act of record keeping yet again, and introduced standardised forms that contained headings and columns, not only making it easier for the parish clerk to record the events in his village, but also making it easier for us hundreds of years later to trace our ancestors! From January 1813 until civil registration in September 1837, these new parish register forms were used throughout England.

Above: A page from the parish baptism book of Woodchurch, Chester, using the new forms. Now with headings above and columns to fill in, we are given a lot more information about our ancestors. These new forms recorded both parents’ names (previously some parish clerks recorded only the father), the place where the family were living, the occupation of the father, and the name of the parish priest who performed the baptism. Sometimes, next to the baptism date, the actual date of birth was also recorded, showing us that it was common for older children to be baptised, or for several children belonging to the same family, to be baptised on the same day.